Marisol: Why do you do this for us?

Stranger: Why? Because I knew someone like

you once and there was no one there to help.

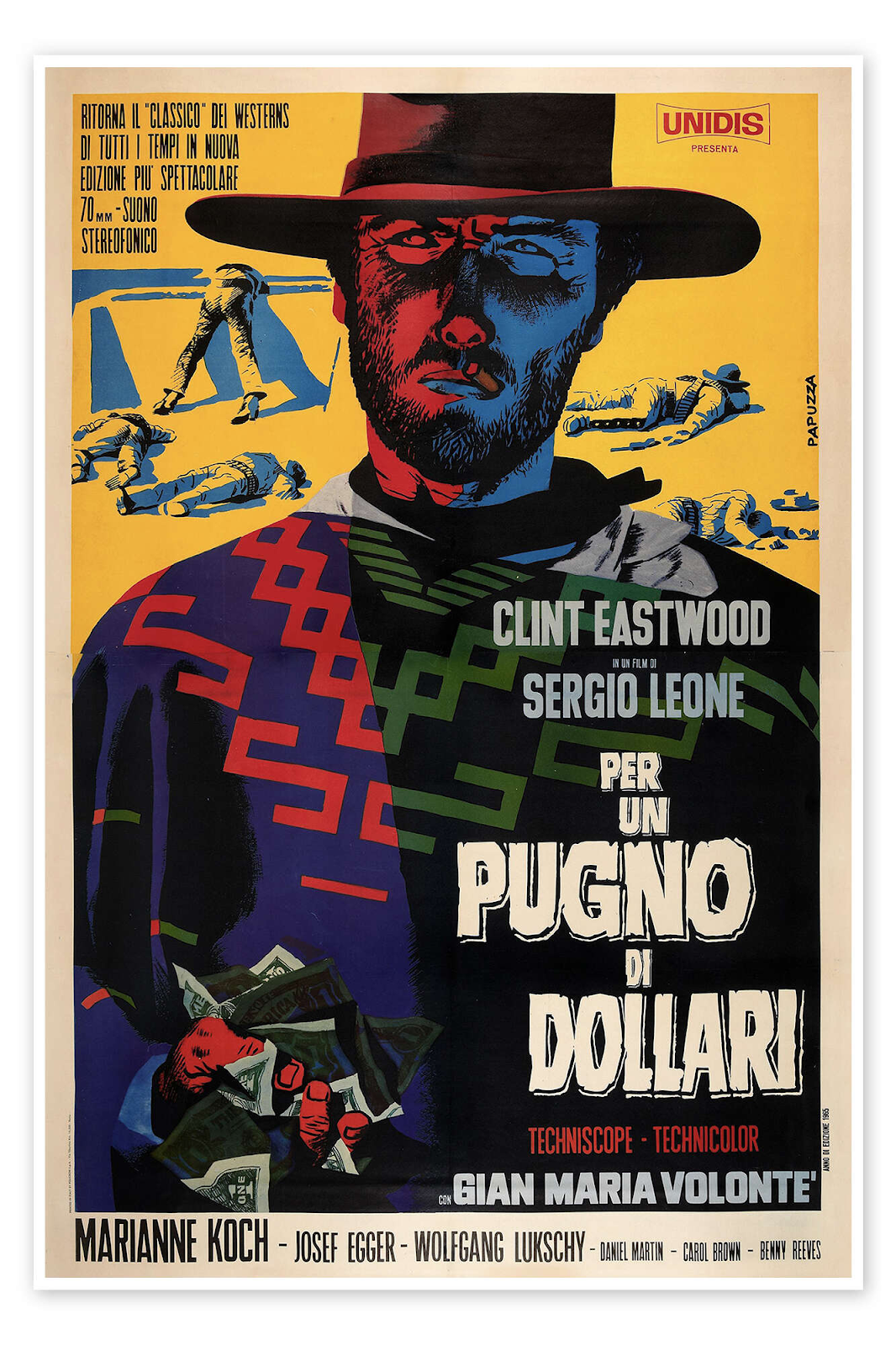

This, this is where IT started.

What is the IT of that sentence?

Well, try this on for size.

The beginnings of Clint Eastwood as icon and not mere,

“Didn’t he used to be on Rawhide?”

It’s hard to imagine now, but there was a time when

nobody really knew the name.

Clint was the tenth choice. Tenth!

First in the roster was Henry Fonda, then Charles

Bronson, then Henry Silva, Rory Calhoun, Tony Russel, Steve Reeves, Ty Hardin

and then James Coburn. These far better known [at the time] American actors all

said, “No, thanks.”

Leone turned next to Richard Harrison, who also took a

pass but Harrison, who was also not impressed with the script, suggested little

known Clint Eastwood who could at least “Look convincingly cowboy.”

Leone, pressed for time, took a chance.

Watch that opening scene, hell, watch the entire film,

does this look like a tenth choice performance?

Laconic swaggering cool never had it so good.

Bonus: Watch Clint’s gun-handling, from drawing, good

wrist, and holster return. He’s doin’ it all. No less an authority than Nicole “Fastdraw”

Franks gives Mr. Eastwood high marks for pistolry depiction.

Eastwood bit at the script, recognizing it as a take

on the chambara film, Yojimbo, with a bit of Dashiell Hammett’s Red

Harvest thrown in.

He picked up his own costume in a Hollywood thrift

store and flew to Europe for this low-budget production by a no-name director,

with this non-marquee star.

This film is also the beginning of Sergio Leone as a

visual stylist that would go on to shape how action is framed.

Consider this, Leone had only directed a single film

before this one, the not well received peplum The Colossus of Rhodes.

There is nothing in that film, nothing, that says “Greatness is to come.”

He directed a mere handful after this film but each of

these from unusual framing, to tracking action with a fluid camera in the days

before Figg Rigs, drones, and light handhelds, in the days when such camera gymnastics

were H-A-R-D—he did it anyway.

The static drawn out calm before the storm action pieces

that have been cribbed by anyone and everyone including Mr. Tarantino who sings

the praises of this film and its two follow-ups as The Only Perfect Film

Trilogy in cinematic history.

The visual cribbing goes way beyond the screen. There

is not a comic book, film poster, or graphic novel that does not owe a tremendous

debt to Mr. Leone’s framing.

This film is really where the soundtrack and film

score as part of the film moves to the fore.

Sure, we have memorable film music prior to this—Bernard

Herrman’s work in Hitchcock’s Psycho being a memorable high point.

But it was composer Ennio Morricone and Sergio Leone

who began something that had not been done before, they made the score a

character in the film.

The score introduces characters. The score dictates

the pace of the scene. The score matches film editing in syncopation—such as it

had not been done before.

This film began anti-hero cool. This film launched a

genre.

This film inspired thousands of films, books, TV

shows, comic books, graphic novels, film scores, fashion trends etc. whether they

were overtly Western or not.

The film viewed in isolation with no context holds up

damn well.

But…if one goes in with an informed eye, an eye that really

looks at everything that is on the screen [I mean everything] an ear that

listens to all.

Then, and only then do we see not something of mere historic

significance in the arts. We see something that is still crafted far better than

much of what we see today that has far better budgets, far better gear, and far

better tech.

What the present imitators don’t have are the maverick

“Let’s go for broke and make our own thing” brio of the trio of Leone,

Eastwood, and Morricone.

And to think this is merely the first film of an ever ascending

trilogy.

Remarkable.